Table of Contents

Humankind has always been drawn to the stars, seeking to understand our place in the vast cosmos. For millennia, our naked eyes were our only tools, but with the invention of the telescope, a new era of discovery began. These ingenious devices don’t just magnify; they are sophisticated light-gathering machines that have unlocked secrets from the farthest reaches of the universe.

So, how do these incredible instruments work their magic? Let’s delve into the fascinating science behind telescopes.

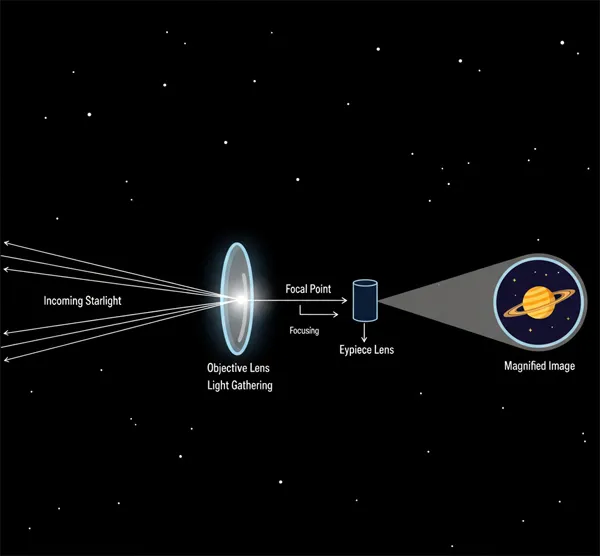

The Fundamental Principle: Gathering and Focusing Light

At its core, a telescope has one primary mission: to collect as much light as possible from distant objects and then focus that light into a clear, magnified image. Our eyes are limited by the size of our pupils, but a telescope acts like a massive artificial pupil, vastly increasing our ability to “see” faint, distant celestial bodies.

This process relies on the properties of light and how it interacts with lenses and mirrors. The larger the primary light-gathering component (whether it’s a lens or a mirror), the more light it can collect, leading to brighter and more detailed views of nebulae, galaxies, and planets.

The Two Main Types of Optical Telescopes

Telescopes achieve light collection and focusing primarily through two different optical designs:

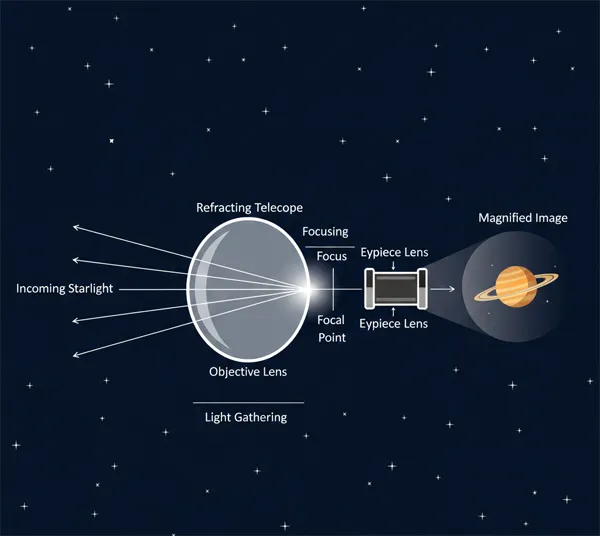

1. Refracting Telescopes (The Lens Masters)

Refractors use lenses to bend (refract) light. Light enters through a large objective lens at the front of the telescope. This lens is convex, meaning it bulges outwards, and it converges the incoming parallel light rays to a single focal point. An eyepiece lens then magnifies this focused image for the observer. Galileo’s first telescopes were refractors.

- Pros: Generally require less maintenance, robust construction, and excellent for planetary viewing due to sharp contrast.

- Cons: Can be very heavy and expensive for large apertures, and susceptible to “chromatic aberration” (color fringing) where different colors of light focus at slightly different points.

A diagram showing the refraction of light:

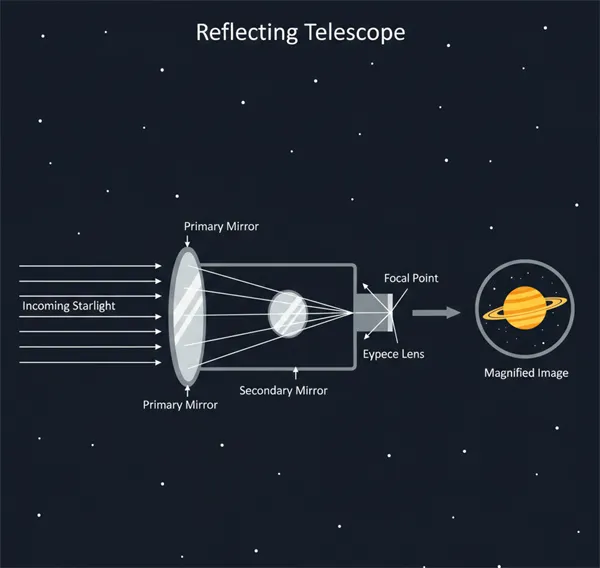

2. Reflecting Telescopes (The Mirror Mavens)

Reflectors use mirrors to bounce (reflect) light. Light enters the telescope tube and strikes a large, curved primary mirror at the back. This mirror focuses the light to a secondary mirror, which then directs the light to the eyepiece. Isaac Newton developed the first practical reflecting telescope.

- Pros: Can be built with very large apertures (excellent for deep-sky objects), no chromatic aberration, and generally more affordable for their size.

- Cons: Mirrors may require occasional alignment (collimation), and the secondary mirror can cause a slight obstruction to the incoming light.

An illustration of light reflection in a telescope:

Beyond Basic Optics: Why Space Telescopes?

Even the largest ground-based telescopes face a formidable obstacle: Earth’s atmosphere. The air we breathe, with its varying temperatures and turbulence, blurs the light from distant objects, causing stars to “twinkle.”

This is why we send telescopes like the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope into orbit. Above the atmosphere, they can capture incredibly sharp, crystal-clear images, observing wavelengths of light that would otherwise be absorbed by our planet’s protective blanket. They truly offer an unfiltered view of the universe, acting as our eyes on the cosmos.

Imagine sitting under a clear night sky, your telescope pointed towards the shimmering Milky Way, ready to reveal its wonders: